Ro-the Japanese sculling oar

Though not a boat per se, the ro, or Japanese sculling oar, is worth discussing as the primary means of propulsion along with the kai, or paddle, for traditional Japanese boats. Some cruising sailors in the West have adopted this oar for use in moving boats up to thirty feet long. It is a very powerful tool and easy to use once you get used to it. If you are interested in learning more about how cruising sailors have adapted the Asian sculling oar, do a Google search on the Chinese variant called the yuloh. Very little has been published on the Japanese ro.

Like much of Japanese art and technology, the ro is almost certainly a product of ancient China. A number of scholars have placed the invention of the yuloh as the Yangtze basin of south-eastern China. The late China scholar Joseph Needham identified paintings showing the sculling oar as far back as the Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD), and two Japanese scholars have argued that the sculling oar may have come to Japan during one of two great migrations of Chinese culture: the introduction of rice cultivation around 100 BC; or during the Nara Period (710 – 794), when Buddhism entered Japan. I have not travelled extensively enough in China to speak with authority on the yuloh, except to say that in general the yuloh seems shorter than its Japanese cousin and is used with a much quicker cadence. As with so much of Japanese culture that came from China and Korea, the Japanese have developed their sculling oar to the point where it is now significantly different from its forebears.

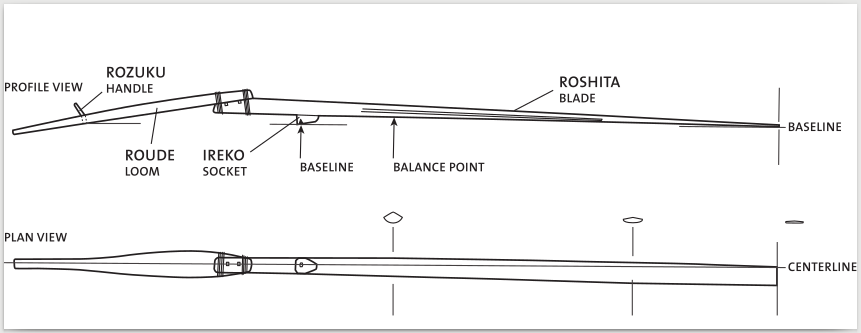

Ro are almost always made of four pieces: the blade (ro-shita), the socket (ireko), the ro-ude (loom), and the handle (ro-zuku). The handle and loom are joined at an angle with a floating tenon bound with either hemp line or wire. The version I built has a floating tenon and bolts together so it can be broken down into two pieces for convenience. The joint is also slightly offset so that the longitudinal centreline of the blade is slightly askew of the handle. The most common location for the ro is to the port side of the stern of the boat, and the socket drops onto a small post (rogui) made of either hard oak or iron. The asymmetry of the handle is to move it inboard slightly from the side location of the pivot. Finally, a rope (hayao) is fastened to the bottom of the boat and a loop is thrown over the handle. On larger boats rogui are mounted on athwart-ship beams that cross the boat at the sheer.

The two main types of ro are tomo-ro (stern mounted) and waki-ro (side mounted). Varieties of Japanese oak are usually used to make ro. In the Tokyo and Osaka region white oak is used for the handle, loom and socket while red oak is used for the blade. In northern Japan a wood called asuza is used for the blade. There is an advantage to using the heavier woods in the blade as the balance of the ro is critical, and a ro with a blade that sinks is advantageous.

The geometry of the ro is critical to its success, and a myriad of factors decide an individual ro’s design. The length of the boat, the height of the rogui off the water, the height of the oarsman, and the conditions of use all have to be taken into account. The heavy section of the loom, for instance, is to give the overall ro the proper balance. Traditionally in urban areas ro and kai were not made by boatbuilders. Ro-craftsmen developed their skills over years of experience and understood their customers’ needs. In the countryside this was not a separate craft and boatbuilders did make ro and kai. It is difficult to come up with standard dimensions for ro since every boatbuilder I have talked to has a different formula. Two Japanese researchers mention a length range of 1.5 – 2.1 meters for the loom and 4.2 – 5.5 meters for the blade. A boatbuilder on Lake Biwa told me that the ratio of distance from the end of the loom to the socket and from the socket to the blade tip should be 5.4 to 10.

The drawing shows the dimensions for a ro built by one of my teachers, Mr. Kazuyoshi Fujiwara, a fourth generation boatbuilder from the Sumida-ward of Tokyo. In the 1990s he heard that the last ro-craftsman of Tokyo was retiring and Fujiwara, recognizing that loss, apprenticed with him. The teacher at the time was in his eighties and the student was in his late sixties. Fujiwara’s ro was made for a replica boat that he and I built together in 2002. It is a chokkibune, a type of Tokyo water taxi.

Using the ro is a revelation. I have sculled the chokkibune many miles and I can say that it takes far less energy to do so than had she been powered with anything like western oars. She is a heavily built boat, over thirty feet long, yet I have sculled her fully loaded with passengers with next to no physical strain. Once one gets comfortable with the ro, the action is a forward and back lean on the balls of one’s feet, using the large muscles of the thighs more than the arms and shoulders. The most basic mistake of the beginner is to feather the blade incorrectly and generate lift instead of thrust. The ro will immediately pop off its post and it is heavy enough that it will take some moments to set it right again. I saw a rental fleet in Japan that had a wire bale looped over the ro at the socket for just this eventuality.

But once under-way the benefits of the Japanese sculling oar become apparent. First, unlike oars that spend half their time in the air on the return stroke, the ro is applying almost constant thrust. The only moment when it isn’t is the fraction of a second at either end of the stroke. The angle of the handle means that the user does not have to physically twist the blade – since the handle is not on the centreline of the blade it automatically rotates. Furthermore, the socket is carefully rounded to aid the rotation. The rope leader is always kept taut, and it counteracts the amount of twisting force. The end of the handle when sculling describes an arc limited by the rope. At slow speeds the rower has to concentrate on lifting slightly to keep the rope taut, but once blade begins to bite, its thrust keeps the handle lifted. Perhaps the most important feature of the rope is that it resists the thrust being applied by the blade. With western oars the force of the thrust is borne directly by the rower with the arms and shoulders. With the ro the thrust of the blade acts to lift the handle, a force that is held in check by the rope. It’s a good thing, since the surface area of the ro is far larger than a pair of standard oars, and a lot of thrust is being created. The only time the ro is ever lifted from the water and feathered like a western sweep is when turning. Then the handle is pushed down, the rope falls slack, and the stern is essentially rowed around. In multi-ro boats the oarsmen do not necessarily have to keep the same cadence, however the side-to-side rocking of the rower when sculling at high speed can begin to rock the boat. Because the ro works astern a boat can be navigated through a waterway just a bit wider than its own hull. Because its long blade can reach four to five feet deep, the major disadvantage of the ro is that it cannot be used in shallow waters; but then again, that is why Japan's boatmen are so expert with their paddles.

Note: This post is an abbreviated version of my article "A Different Way to Ro" published by WoodenBoat Magazine, Issue 192, September/October, 2006.

© Copyright Douglas Brooks, 2007 - 2018. All rights reserved